|

Several years ago, likely after the events of 9/11, I began to hear a call to renew or return to the language of lament within our worship. It was such a novel idea that I had no conception of what lament should look like within any shape of liturgy. But it was Don Saliers who first gave me the freedom to find such an expression and necessity in the language of our liturgies. This project has given me another opportunity to explore the language of lament and in particular the questions of complaint that the psalmist posed, not just to God, but at God.

Saliers thoughts are directed toward the shape and theology of our liturgies and how the language of lament forms an essential component of our worship. In his view, “Christian liturgy transforms and empowers when the vulnerability of human pathos is met by the ethos of God’s vulnerability in word and sacrament.”[1] Truly authentic worship lifts up human reality, in all of its complexities and roughness to transformation by the Holy Spirit. Liturgy without lament would seem to ring false, becoming “anorexic, starving for honest emotional range.”[2] And yet, it is so often left out or even suppressed from our worship language. Perhaps their omission is rooted in a fear of sinfulness, unfaith, or an overwrought politeness that these questions concerning the brutality of human experience in the light of God’s promised goodness and past actions, are rarely given full exploration. Simply put, “lament is seen as a negative way of speaking, unfitted for a prayer to God.”[3] Unfortunately this has resulted in our ecclesial communities losing the language of lament, it may serve as a corrective for those that wish to withdraw from life as it really is, to pretense and romance in the unreal world of heavenly or holy things.”[4] What struck me was that we are so incredibly polite with God. At times, this is rightly so. But there is also a confidence that our faith brings, combined with out utter neediness that we may boldly approach God baring the ugly realities of all that is wrong to the only One who can set things aright. The psalmist’s testimonies left nothing out of their purview: praise and bitterness, hope and fear, life and death. And a good number of psalms emerging from this emotional gamut also contain brute and penetrating questions of Yahweh: Why? Where? How long? Saliers says that their laments (and these questions of complaint) are firmly rooted in the covenant, utilizing memory of the individual and community of God’s past actions. But more provocatively, they remind God of God’s own past actions. In other words, they remind God to be God.[5] These questions posed to and at Yahweh, emanate from the individual or communal nerve rubbed raw, furnishing an expression of Israel’s deepest needs and concerns in response to Yahweh’s personal invitation. Hans-Joachim Kraus speaks of the summons: Yahweh himself calls to the men and women of Israel and invites them, ‘Seek ye my face’ (Ps. 27.8)… ‘Call upon me in the day of trouble’ (Ps. 50.15). The call and invitation are accompanied by God’s promises, ‘I will deliver you’ (Ps. 50.15); ‘Fear not, I will help you’ (Isa. 41.13). Yahweh’s word opens the way to petition and thanks. The one who comes to pray comes in the assurance of God’s help. Therefore the institutions of worship bare the sign of God’s accessibility.[6] But this “open way” and “accessibility” of Yahweh also opens the proverbial door to more than Israel’s petitions and thanks. At times, Israel takes advantage or opportunity of Yahweh’s accessibility and vulnerability in their intimate partnership, to question Yahweh in the disparate light of experience and covenant. This exchange clearly shows that “biblical faith, as it faces life fully, is uncompromisingly and unembarrassedly dialogic.” [7] Brueggemann contrasts Israel and Yahweh’s dialogical partnership with how “gingerly” this reciprocity is treated today in the church. He states, "If we are dialogic at all, we think it must be polite and positive and filled only with gratitude. So little do our liturgies bring expression to our anger and hatred, our sense of betrayal and absurdity. But even more acutely, with our failure of nerve and our refusal to presume upon our partner in dialogue, we are seduced into nondialogical forms of faith, as though we were the only ones there; and so we settle for meditation and reflection."[8] Ultimately, our biblical example of Israel’s interactive expression with Yahweh is based in their intimate relationship which gives rise to profound questioning of Yahweh. The lament and complaint simultaneously give “witness to a robust form of faith that affirms that God seriously honors God’s part of the exchange”[9] as well as, the worth of humanness and our experience. Human experience in a fallen world is sure to encounter that which seems unfair and disproportionately wrong. But these laments and complaints give free expression to that which is overwhelmingly incongruent and are not just petty or trivial whining about their condition. Israel saw within their respected relationship with Yahweh, the right to come before the Lord and make complaints and protests grounded in covenantal faithfulness. Israel refused the mute acceptance of their conditions as “God’s will” as so often found in our spiritual vocabularies today. Nor were these vigorous protests to Yahweh acts of unfaith, but vocalized uprisings of their freedom and responsibility. [1] Don Saliers, Worship As Theology: Foretaste of Glory Divine, (Nashville, Abingdon Press, 1994), 22. [2] Ibid., 121. [3] Claus Westermann, The Living Psalms, (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989), 67. Westermann notes that since the middle ages and into the more recent times, “most people generally regarded suffering as a consequence of sin and a punishment for sin” (67). [4] Walter Brueggemann, The Psalms and the Life of Faith, ed. Patrick D. Miller, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995), 67. Elsewhere Brueggemann says similar things, “It is my judgment that this action of the church is less an evangelical defiance guided by faith, and much more a frightened, numb denial and deception that does not what to acknowledge or experience the disorientation of life. The reason for such relentless affirmation of orientation seems to come, not from faith, but from wishful optimism of our culture.” (Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary, (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984), 51. [5] Saliers, 35. [6] Hans-Joachim Kraus, Theology of the Psalms, Translated by Keith Crim, (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing, 1979), 141. [7] Brueggemann, Psalms and the Life of Faith, 68. [8] Ibid., 68. [9] Ibid.

0 Comments

This is a rather later addition to the Fight Club series, but upon reading The Rule of Saint Benedict this week one short passage stood out, as if I had seen a mirror of this in action recently.

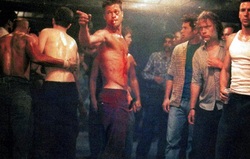

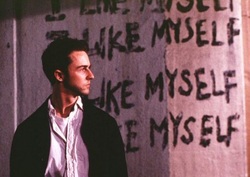

Rule 58 states, “When anyone presents himself to be admitted as a monk, they shall not easily give him entrance; but, as the apostle advises: ‘Make trial of the spirits, to see if they are of God’ (1 John 4.1). If he is importunate and goes on knocking at the door, for four or five days, and patiently bears insults and rebuffs and still persists, he shall be allowed to enter. He shall stay in the guest-room for a few days.Thence he shall go to the cell where the novices study and eat and sleep.” This Benedictine initiation practice is meant to deter those who are not prepared to undertake such a life change. This is not meant to be easy. After several days of waiting through insults and denials, they still persist in their desire, they may be allowed to enter. I have heard of a Rabbinical tradition that may do similar things. Those who wish to convert to Judaism approach a Rabbi who rebuffs them. If they return three times, they may undertake with seriousness their conversion.In Fight Club, we see young men coming to stand outside on the porch of the Paper Street house waiting to enter. They are verbally and physically harassed about being to young, fat, or blonde. Once they have stood the appropriate time, they are asked if they have brought the needed supplies of black clothing and personal burial money. Once entered they receive a ritualistic head shaving, thus leaving their old beauty of the world behind. They form a new army and take on its uniform. I wonder how many American Christians would actually put up the waiting and rebuffs to become a Christian? Does the Church allow too easy of conversion? Would any church actually rebuff someone today who came seeking? What can our churches learn from the novitiate or catechumenate processes?  When I originally wrote this our small group had been studying the Gospel of Luke for the previous 6 months or so and we continually returned to Luke 4:16-21 as a hermeneutical lens for understanding Luke’s perspective of Jesus. The passage states, “When he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, he went to the synagogue on the sabbath day, as was his custom. He stood up to read, 17 and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written: 18 "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, 19 to proclaim the year of the Lord's favor." 20 And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. 21 Then he began to say to them, "Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing." The scroll was open to Isaiah 61 which should be read a fuller understanding for this context but Jesus’ own words suffice as a summary. Verse 19a of the Luke passage or 2a of Isaiah 61 mention the “year of the Lord’s favor” which points to the Year of Jubilee in Leviticus 25 where all property shall be returned to its rightful owners and debts are forgiven. With that in the back of my mind, my recent viewing of Fight Club radically changed my perception of Tyler Durden. Kelton Cobb, in The Blackwell Guide to Popular Culture states that "Jack" apprentices Tyler’s in an “ad hoc twelve-step program that Tyler devises to free Jack from his bondage to the dominant paradigm of consumerism” (p. 11). I began to wonder, is Tyler a sort of Christ figure, albeit a very dark one? Much of what the Lukan passage suggest and recurs throughout the Gospel is liberation from illness, oppression and the structures of society. Tyler is trying to liberate Jack and subsequently the rest of the men (and also the participational viewer) from the burden of branded identities and consumption. Tyler whispers to Jack while he is on the phone with the police, “Tell him the liberator who destroyed my property has realigned my perception.” Another telling scene is in the basement of Lou’s bar or tavern. Lou enters and proceeds to pummel Tyler. Tyler willingly accepts this beating for the sake of others. Tyler motions to "Jack" to stay on the sidelines because his entry would derail his purposes of obtaining this venue on behalf of the greater whole. He, like the Space Monkeys later sacrifice themselves so that fledgling community of Fight Club may go on. Another telling scene takes place in the back of a convenience store…the epitome of unnecessary consumption. With the glow of soda machines in the background the store clerk, Raymond K. Hessel is hauled out at gunpoint and made to kneel on the ground. Tyler sifts through his wallet finding an expired community college I.D. card he asks what he studied. The clerk, fearing for his life manages to dribble out barely understandable words. At one time, he had wanted to be a veterinarian and having become overwhelmed by the work involved he left his dreams behind to work in a life-sapping environment of consumption. Tyler takes the man’s license and says that he will check in on him in 6 weeks and will kill him if he is not on the way towards becoming a veterinarian. Afterwards Tyler says, “Tomorrow will be the most beautiful day in Raymond K. Hessel’s life.” Raymond is awoken from the slumber of self in a society bent on selfish consumption and freed to pursue his dreams. In fact, his life (both metaphorically and literally) depend upon it. In a later scene, we see the back of a door covered with stolen drivers licenses signifying that this was not a random act. Rather they had encountered many attempting to liberate them from consumption towards a greater good. Another central question that should be asked is the nature of the violence. To what end is the violence. Is there meaning in or redemption from the violence? In these particular scenes it would seem that there is. The cross, the supreme act of violence in the Christian tradition becomes the central motif for Paul and the means of our salvation. Here too the violence is the necessary method of freeing others from the oppression of social structures. Raymond K. Hessel and all the others represented by their drivers licenses have been in someway freed. The Space Monkey’s too have been freed from their miserable lives to find meaning in liberating others. And we as the viewer also are to find liberation by participation in the story. Tyler may be thought of a sort of Christ-figure insofar as he gives sight to the blind (awakens slumbering culture to the effects of consumerism) and then heals them by giving them a new identity, and brings good news to the poor (both literally poor and of spirit), and frees them from the burden. The clincher for this Christological lens is the year of the Lord’s favor…the Year of Jubilee. Tyler, and project Mayhem are bent on bringing down the credit card industry to level the economic playing field. By destroying this harmful and oppressive banking practice Tyler initiates what to many would be the Year of Jubilee. And yet, we must consider (as one of my students pointed out) not only what Tyler is liberating them from, but to what/where are they going? And this is where the Christ-figure lens would seem to fail. Robert Bellah points out a fantastic irony in Habits of the Heart by saying, “just where we think we are most free (we’ve cast off these oppressive structures and philosophies), we are most coerced by the dominant beliefs of our own culture. For it is a powerful cultural fiction that we not only can, but must, make up our deepest beliefs in the isolation of our private selves” (p. 65). Radical individuals fail to see that they cast off one set of traditions for another set. Thus Tyler leads them from the oppressions of one tradition (namely consumption) to another (namely violence and anarchism). If this is correct and the film finally does not endorse the violence it portrays,Tyler can simultaneously be thought of as an anti-Christ leading his followers into another form of oppression.  The Hegelian synthesis suggests that from a thesis will arise its anti-thesis and as a way to mediate between the two, a synthesis will emerge by blending and rejecting elements of both the thesis and antithesis. Fight Club, while giving voice to the frustrations of many post-moderns, seems to utilize this very modern construct. The thesis is represented by Edward Norton’s character "Jack" or the Narrator as a buttoned-down un-happy white-collar worker in an un-ethical and mind-numbing job. His antithesis, Tyler Durden, played by Brad Pitt is the alpha-male unrestrained by societal rules and its ways of functioning. Tyler is Jack’s self-created, self-liberating alternate personality. For this to work we must ask, does the film ultimately condone the violence of Tyler’s actions as they are portrayed? The final scenes would seem to give us ample direction to say that the violence portrayed is not the ultimate answer. The Jack at the end is no longer the slave to the Ikea nesting instinct he was at the beginning and yet neither is he the slave to Tyler’s ambitious anarchy. Jack in the final scenes would seem to represent the synthesis. He has been liberated from desire for consumption but also its antithesis of violent rejection. He is not the emasculated male nor the hyper-violent male either. I think we see the synthesis at work in Tyler’s words too. On one hand he says that “You are not your khakis” but also, “You are not special. You are not a beautiful or unique snowflake. You are the same decaying organic matter as everything else. We are the all-singing, all dancing crap of the world. We are all part of the same compost heap.” Robert Bellah in Habits of the Heart describes individualism in two particular forms: utilitarian and expressive. Benjamin Franklin is the epitome of the utilitarian expression of individualism where the individual rises to success through hard work and personal initiative. They are identified by the proverbial “pulling oneself up by the bootstraps.” Many believed that if each individual vigorously pursued his or her own interest, the social good would also automatically emerge (p.33). Expressive individualism, a form of Romanticism and best exemplified by Walt Whitman, arose in reaction to the materialistic pursuits of utilitarian individualism. Expressive individualism sought to cultivate the self and self-expression where each person has a “unique core of feeling and intuition that must unfold if individuality is to be expressed (p. 333-4) These sentiments are easily identifiable in Whitman’s writings, as well as, Emerson, Thoreau, Melville and others. For the expressivists, “the ultimate use of the American’s independence was to cultivate and express the self and explore its vast social and cosmic identities” (p. 35). We hear this in our language of “finding oneself.” Fight Club seems to critique both the materialistic utilitarian individual as well as the self-cultivating expressivist. And yet, the film avoids becoming preachy and dictating the synthesis. It is left to the individual to navigate and mediate between the utilitarian and expressivist, as well as the emasculated consumer and ultra-violent alpha male. "Jack" becomes the one who has successfully escaped both but we are left to fill in what his life will now look like.  Most commentators suggest that Fight Club is a nihilistic film likely based in the anarchist and violent tendencies portrayed by Tyler Durden.First we should consider a basic concept of nihilism. Literally it suggests “nothingness” emanating from a “complete rejection of and possibly the destruction of beliefs and values associated with moral and traditional social structures. Philosophically, nihilism represents an attitude of total skepticism regarding objective truth claims. Nihilism views knowledge as dependent upon sensory experience alone, so that moral and theological claims are meaningless” (Stan Grenz,Pocket Dictionary of Theological Terms). In many ways, these ideas are embodied in the film. There is a rejection of capitalism and consumerism that most hold dear in our culture. There is a rejection that violence is bad. Pain, or other sensory experiences becomes the means to awaken to real life. We see that latter with the scarification ritual in the soap-making kitchen. Tyler says, “this is the most beautiful moment of your life, don’t deal with it the way those dead people do.” Which is another critique of the therapeutic tendencies of our culture. That same scene also gives us other insights into the nihilism of the film. Many forms of nihilism are naturally paired with atheism. If there is no God, than there can be no moral absolutes. Tyler’s monologue in the kitchen suggests that this form of nihilism is not atheistic. “Our fathers were our models for God. If our fathers bailed, what does that tell you about God? You have to consider the possibility that God does not like you. Never wanted you, and in all probability he hates you. this is not the worst thing that can happen. We don’t need him.Fuck damnation, man. Fuck redemption. We are God’s unwanted children. So be it. It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we are free to do anything.” Kelton Cobb in The Blackwell Guide to Popular Culture states, “This is a bitter theism, a resentful affirmation of God’s existence” (p. 265-6).God seems to be a given. And yet we are forced to contend with the apparent realities of life rather than what we would like to believe about God. His experience colors his concepts of God. In return, he renders God as irrelevant. The article on Nihilism from the Encyclopedia of Philosophy edited by Donald M. Borchrt also suggested, “nihilism is caused not so much by atheism as by industrialization and social pressures, and its typical consequences are not selfishness or suicide, but indifference, ironical detachment, or sheer bafflement.” This claim certain helps see the effects of consumerism as an institutional violence. And yet, the nihilism portrayed in Fight Club is not absence of hope.Tyler says to "Jack", “In the world I see, we’re stalking elk in the grand canyon around the ruins of the Rockefeller Center. You’ll wear leather clothes that will last you the rest of your life. You’ll climb the vines around the Sears tower. And when you look down you’ll see tiny figures pounding corn, laying strips of venison on the empty carpool lane of some abandoned superhighway.” Kelton Cobb states, “For Tyler, Eden will rise from the rubble of cities that have been cleansed of the poison of corporate logos, global markets and consumer incompetence” (p. 265-6). Furthermore, if there is no hope and no meaning, why bother with the destruction of society to liberate humanity? In many way’s the film is nihilistic. And yet there are glimmers of hope not unlike our eschatological hope. Times are dark and yet we can see and imagine a purer reality as it has been promised, and in some ways is already present.  Emasculation becomes a central theme in Fight Club as it is portrayed by the narrator Jack. William Romanowski, in Eyes Wide Open states, “Emasculated by the consumer culture…Jack finds solace (though under false pretense) in a support group for men with testicular cancer: (The castration metaphor is obvious.) There he meets Bob, a former body builder; who has developed feminine features resulting from his cancer treatment. Trying to comfort the sobbing Jack, Bob rasps in a high pitched voice, ‘We’re still men,’ with Jack affirming “Yes, we’re men. Men is what we are.”Consumer culture emasculates by fostering false idealized images that motivate men to change what and who they are: men. They run longing for this idealized image to which Tyler, Jack’s idealized alpha-male alter-ego helps to free Jack from this burden. At the outset of the film we find the emasculated Jack seeking solace and identity in consumable products rather than in himself…whatever that may look like. In an early scene where Jack and Tyler first appear in the same shot, sitting side by side on the airplane Tyler reads the emergency instruction card to which Jack replies something about the great responsibility that seat has to open the emergency door. Tylerasks if he would like to switch seats to which Jack replies, “I’m not sure that I am the man for that job.” Lack of confidence, or sense of responsibility Jack declines as a symptom of the emasculated male. In one scene Jack describes the relationship between he and Tyler as, “Most of the week we were like Ozzie and Harriet.” We are not confused who is whom in this analogous pairing. In another scene at Marla’s apartment, Marla says to Tyler, “Oh Don’t worry he’s (referring to a dildo) not a threat to you.” As the alpha-male, sure of his virile sexuality, Tyler is not threatened by a wobbling gelatinous penis on the dresser. And yet, earlier when Jack, the emasculated male is at the airport, the attendant insinuates that Jack’s missing luggage may have been a result of a vibrating dildo. Craig Detweiler in his book, A Matrix of Meanings says, “A longing for God and fathers informs every frame of Fight Club” (p. 42.). We see this theme boy with out father-figures recurring throughout the film. In a later poignant scene, the two men sit and discuss their fathers. Jack: “I can’t get married, I’m a 30 year old boy.” Tyler: “We are a generation of men raised by women…I’ wondering if another woman is really the answer we need.” Elsewhere in the film Tyler asks, “Our fathers were our models for God. If our fathers bailed, what does that tell you about God?” Our culture’s lack of fathers point of orientation in development renders an incomplete identity that must be filled by things. Ultimately the we are shown what it means to be a man by those products rather than our fathers. Jack narrates to the audience, “I felt sorry for guys packed into gyms, trying to look like how Calvin Klein or Tommy Hilfiger said they should look.” And turning to Tyler asks, “Is that what a man looks like?” Later Tyler responds to similar thoughts in a monologue to the local fight club, “Man, I see in fight club the strongest and smartest men who've ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see squandering. God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables; slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need. We're the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War's a spiritual war... our Great Depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won't. And we're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off. We have been sold a false bill of goods and the scales have fallen from our eyes. The mute now have a voice to combat the culture…to give an expression to their (and ours) discontent. Tyler represents Jack’s desire to be a strong male rather than the passive slave to culture. And we are left to ponder our own emasculation. Are we simultaneously repulsed by Jack’s emasculation and attracted to Tyler’s freedom? If so, is that symptomatic of our own emasculation? This is your new blog post. Click here and start typing, or drag in elements from the top bar.

Fight Club is one of my all-time favorite films. Period. Over the next week or so I will be re-posting a series of thoughts on the film from my old blog. I saw the film first in 1999 when the film came out. It was against the advice of a good friend who was thoroughly disappointed with the lack of fighting. He had hoped that it for a boxing movie to which Fight Club is sure to disappoint. The film is certainly violent, but it serves a different purpose than a film like Rocky where the hero rises against the odds to greatness. Fight Club uses violence as a subtext to explore what is necessary to subvert the dominant paradigm of consumption. Fight Club is a scathing critique of our branded and consumable identities. The Narrator played by Edward Norton, who remains nameless save a few 3rd person references as “Jack” is shackled by societies addiction to things. The fact that he largely remains nameless is suggestive of two things: 1) that he finds his identity in those things he buys and 2) Jack is a sort of everyman in which we are to see that we too are kept by these consumeristic desires. In response to the question of police about the destruction of his apartment, Jack states, ““That condo was my life. I loved every stick of furniture in that place. That is not just a bunch of stuff that got destroyed, it was me!” It was ME! His identity had become those things. In a consumer culture we can buy our identity, change it on a whim because we are buying not simply clothes or furniture but a lifestyle that tells others about who we are. For Jack, identity was found in his stuff…his Ikea furniture, his AX ties and DKNY shirts etc.In one poignant scene Jack tells Tyler, “I had it all. I had a stereo that was very decent, a wardrobe that was getting very respectable. I was close to being complete.” To which Tyler replies casually, as if unbound to all forms of materialism, “Shit man, now it's all gone.”Jack’s identity was almost complete as if there is nothing of value within the self but must be supported and comforted with commodities and now, it was all gone. Without these material enhancements, Jack must now set out on a path of discovery towards who he really is. In that same poignant scene come the most scathing critique of consumerism. Tyler Durden: Do you know what a duvet is? Jack: It's a comforter... Tyler Durden: It's a blanket. Just a blanket. Now why do guys like you and me know what a duvet is? Is this essential to our survival, in the hunter-gatherer sense of the word? No. What are we then? Jack: ...Consumers? Tyler Durden: Right. We are consumers. We're the bi-products of a lifestyle obsession. Murder, crime, poverty, these things don't concern me. What concerns me, are celebrity magazines, television with 500 channels, some guy's name on my underwear. Rogaine, Viagra, Olestra. Jack: Martha Stewart. Tyler Durden: Fuck Martha Stewart. Martha's polishing the brass on the Titanic. It's all going down, man. So fuck off with your sofa units and string green stripe patterns. Here we get a glimpse of the final scenes of the film. That this cultures ways of consumption, this lifestyle obsession is coming to an end. We are left to wonder now in retrospect, does Tyler already have his plans in mind? This is also telling for Christians who are just as easily sucked into our cultures consumptive ways. We too are more interested in the personal enhancements, the versatile solutions for modern living, than issues of social justice. Certainly the health and wealth gospel only serves to uphold the cultures consumption.Messages of service and sacrifice, the Cross and martyrdom are sadly out of fashion. If we are to critique our culture which in embedded in consumption, we must also provide a viable alternative in which we locate our true identity. Which the church has: the story of God in Israel and Christ.And yet, we must be careful not to package and sell the story in the medium of that same consumeristic culture. It is a telling irony, thatTyler’s anti consumption task force, Project Mayhem is funded by consumption or their selling of designer soaps. It points out the irony that anti-consumerism can still be sold as a product or identity. Jack says, “It was beautiful, we were selling rich women their own fat asses back to them.” The Christian faith is not another add-on identity to those we have already garnered. It is something other. Something that demands the whole self. Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2004

While many would agree that animals have been significant to human life and society, few could articulate these dynamics as well as Virginia DeJohn Anderson has done in Creatures of Empire. Building on the insights of environmental history, Anderson creatively turns to focus on the role of animals within the relational dynamics between the early American colonists and Native-Americans. She eloquently argues that both Natives and Colonists were guided by distinct cosmological views that deeply guided their agricultural practices. Negotiating these differences became key as the two groups attempted to live near one another. As a result, Anderson claims, “animals not only produced changes in the land but also in the hearts and minds of the peoples who dealt with them.” [1] Anderson begins by cultivating a landscape of distinct spiritual/cosmological beliefs that guide each groups’ practices with animals. She persuasively argues that Natives merged the physical and spiritual worlds forming a dynamic reciprocity among living and spiritual beings. Conversely, the English rooted their self-understanding as the pinnacle of creation as written in Genesis. A theology of dominion dictated a sharp dichotomy of human and non-human beings leaving humanity as the divinely sanctioned rulers over the land and its creatures. Once this cosmological landscape is set, Anderson turns toward the practices of animal husbandry. Natives had to contend not just with the newly arrived English colonists, but their animals as well. These strange new beasts were slowly integrated into Native vocabulary, worldviews, and practices; but not always in the ways as the English hoped. Guided by their theology of dominion, the English regarded animals as domesticated property and essential to civilized and Christian life. While Animal ownership and husbandry were key markers of civility in English society the imported practices underwent a significant change within the Chesapeake Colonies and Southern New England colonies. A remarkable amount of care and time were given to livestock animals back in England. Anderson works to show how these high standards of practice fell sharply due to constraints of time, workforce and spatial concerns. As a result, animals often had to make their own way ranging freely through the forests and fields. Conflicts arose when the untended English animals trampled their way into unfenced Indian fields damaging crops. Early on, the Indians would kill the offending beasts but since the animals were seen as property to the English, they would demand restitution. Anderson surveys court histories and colonial annals seeking recorded details about the inevitable conflicts. She suggests that the amounts of conflicts were a good barometer of the current state of the relationship between the colonists and the natives. Discussions between the two parties to reduce animal trespasses, Anderson suggests, were a means for both to work out a vision a cooperative life near each other might look like. She is keen on asserting Native agency in this regard. Noting the ironic failure of restitution when Natives destroyed English animals for their destroying their fields, she states how Natives followed appropriate legal procedure for their claims but to an ever increasingly biased community. She argues the Indians ultimately made more concessions than the English who became less willing consider compromise. The provocative turn that Anderson takes from environmental history suggests that English animal husbandry served more than simple agricultural needs. Domesticated animals became a calculated means of extending civilized English life and habits to the New World and its native inhabitants. However, she carefully articulates that often Natives who learned to live with English livestock did so, on their own terms and as a means to remain Native. This was a position the colonists could not understand or allow to continue. Over time, as these methods failed and the need for land increased, the English strategy changed. While animals had always been part of English colonizing and plan for conversion, Anderson claims the colonists would simply allow their animals more leeway in their roaming making expedient means of spreading the Empire in land and ideology. This becomes a sad and ironic pattern that recurred at the edges of Western expansion across the continent that while “Indians found room in their world for livestock…the colonists and their descendants could find no room in theirs for Indians.”[2] My one minor contention with Anderson regards her portrayal of Christianity and the doctrine of dominion in particular. It seems to me that there is an over reliance upon Keith Thomas’ Man and the Natural World to claim how vital a theology of dominion was to colonists’ action with both the land and animals. It is curious to me that while she occasionally quotes colonial ministers, she does not do so to support the theological claim, but rather ethical exhortations to live peacefully with their Native neighbors. Additionally, Anderson too narrowly focuses on the subjection of animals to humanity without equal redress to the ideas of stewardship implicit within Christian theologies of dominion. When she does reference ideas of stewardship, she fails to note if it is a Christian/Protestant virtue or an English ideal associated with the proper practices of animal husbandry. Likewise, she at times seems unconcerned about important distinctions within the church quoting both John Calvin and Thomas Aquinas. Elsewhere, she seems to use Protestantism, Calvinism, and Christianity interchangeably. Christianity, or Protestantism for that matter, is too broad and diverse to be characterized by one doctrine. These are only minor issues that do not detract from Anderson’s overall remarkable trajectory. Creatures of Empire is necessary reading for all interested in Environmental history, agricultural history, and Colonial America. Yet, her writing and claims are engaging for those well beyond specialists in the field as well. [1] Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America, (Oxford: Oxford Press, 2004), 5. [2] Ibid., 246. I’ve been thinking, as much of the nation has, about the terrible events at Penn State. It makes me sick to think of all the pain, anger, frustration, and a host of other emotions that come from these events. I am heartbroken for the children, for the fans, for those who acted but did not act enough, for the families and friends of those involved…and the list goes on.

One thought that keeps coming back emerges from my days in seminary. During my last year at Sioux Falls Seminary, we hosted Dallas Willard and Richard Foster to speak on spiritual development. In particular they spoke of the spiritual disciplines. Foster defined discipline along the lines of “the ability to do what needs to be done, when it needs to be done.” The spiritual disciplines train us to act decisively when action is needed. I come to these thoughts when I consider the graduate student who encountered the coach in the shower with the young boy. His reaction was to retreat to his office and call his father and subsequently Joe Paterno. He did act…but probably not sufficiently. Why did he not stop that horrible event? This is what everyone wants to know. But while we are right to ask such questions, I suspect that many of us have failed to act decisively at times as well. Have we witnessed bullying? Abuse? Humiliation? Intimidations? Did we do anything about it? Sure this case at PSU is certainly worse but there are helpful parallels that we should examine in our own lives. A Facebook friend posted a thoughtful comment on the shame these actions have brought upon the institution. Again this brings me back to Foster’s comments on discipline. Will we have the ability, when under pressure, to act rightly, to not bring shame, to do what needs to be done when it needs to be done? It is easy to stand on the outside of these events and ask pointed and judgmental questions about various inactions in these events. But the question I keep asking myself is, “How would I have responded had I encountered such a shocking event?” I would love to think of myself in the best light that I would have stepped in and stopped the event. I would love to think that I would have followed up on this event and made sure it made it to the police. I would love to think that I would have done the right thing when it needed to be done. But I cannot be sure that I wouldn’t have done something similar to the grad students actions. Call me a coward or whatever…but I simply do not know. What I do know, is that to respond rightly is both a matter of prayer and practice. The disciplines become means of training the right behaviors, affections, thoughts so that we might persevere when times deserve it. They are practiced with the Spirit, retraining us and our thought and action patterns to align with Christ’s. It is a physical and prayerful exercise. My prayer is that my spiritual exercises will leave me well trained on the day that requires decisive action and that I may act rightly, and do what needs to be done, when it needs to be done.  The Man With The Movie Camera was produced in 1928 by Dziga Vertov. Vertov was employed by the MoscowState film studio’s until his films, which were often political manifesto’s about the nature and possibilities of film, fell out of favor with Stalinist Russia. Only under Kruschev in the early 60’s did his films re-emerge.One of Vertov’s tasks was to cultivate a new cinematic language and thus rejecting traditional cinema, particularly Western narrative cinema that drew heavily upon literature and staged acting. He wanted to show the beauty of the actual without the artificiality of stages and actors which function on the presupposition of filmed reality. Vertov attempted to film life as it was or life caught unaware because people act differently on camera than when not in front of the eye. Often considered a formalist, Vertov emphasized the artistic process of filmmaking itself through editing, special effects, camera angle and position in order to capture reality but also suggest an ideal reality. Viewing THWTMC provides an excellent opportunity to gain visual literacy. Vertov utilized the montage, or “two film pieces of any kind, placed together, inevitably combine into a new concept, a new quality, arising out of that juxtaposition.” Vertov is a master at this. Not only as viewers are we forced to contend with the composition and structure of each shot, we must interpret the purposeful sequences of images that may build upon, interpret, or juxtapose past or future images. Vertov is working on a great number of conceptual ideas in this film.We would do well to keep our eyes out for a few key ideas. The film, in one sense, is a statement about film…what it should be and what it should not be. Vertov’s a film is both art and art theory. THWTMC attempts to show an interconnectedness between humanity and machine. Vertov shows the joys of work, the similarity of rhythms between humanity and the city. The city, the machines, and humanity are merged into one larger machine. It is a celebration of the Soviet workers state. Vertov is also attempting to show the that the filmmaker is a key part in this workers world performing similar duties to factory workers that were needed to keep this larger national machine running. Vertov works symbolically through special effects and editing.Watch for the juxtaposition of shots and what they symbolize. Vertov was intrigued with Einstein’s theory of relativity and thus tries to show the relativity of time, space, size, etc. 1) How did Vertov convey the interconnectedness of the city and humanity? 2) How did Vertov show the importance of his own role in society? 3) Which editing sequences did you find most interesting? 4) Do you see this as a narrative piece or non-narrative documentary style film? 5) What similarities does Vertov’s film share with Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi? 6) What are the two filmmakers perspectives on technology? 7) What relevance does Vertov’s work have for us today? View The Man With the Movie Camera online. Another fascinating site is www.dziga.perrybard.net/, an updating ofTMWTMC. By inviting others to contribute similar scenes from their own video collections, the film is recreated and run along side of each other. |

Ryan StanderArchives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed