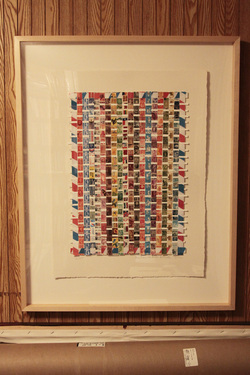

Sometimes getting new art is better than making art. This is a piece we (Sundog Multiples) made last spring for Barton Benes. Ive been waiting to get this one framed and hung for 6 months and finally got it finished today. This is one of Barton's new pieces that integrates stamps into a weaving of sorts like prayer rug.

0 Comments

Corporate Laments and Complaints

We do not tend to relate quite as easily to the communal laments and complaints for a number of reasons. Privatization of our faith caused in part by of our individualism, which I have already noted, renders our corporate identity nearly lost along with any capacity to think theologically about public issues and problems.[1] But the ekklesia is not a collection of isolated individuals consuming a private faith. The church is a public body with an alternative orientation in the world. These psalms remind us of that fact. We are participants within a broken world, a world at whose hands the church often suffers, and the same world we are to be reconciling to God in the name of Christ. Westermann notes that there were typically two sorts of crisis which occasioned the lament: “a political crisis, such as war, enemy attack, destruction of the city or the sanctuary and the deportation of the inhabitants; and the other [being] natural catastrophes such as drought or a plague.”[2] Though within the communal laments, it is almost always the enemies that become the impetus for the psalmist. While the temple and the enemies may not be as easily relatable our context,[3] Brueggemann encourages that utilize a “dynamic analogy” for connecting points.[4] It is an opportunity to do contextualization of the Psalm for similar things on large scales such as war and its losses, destruction done by nature, or and epidemic. It is the language of these psalms that we may and must turn to in solidarity with both a broken humanity or creation and its covenanting Creator. Psalm 74 Psalm 74 is a painful and yet beautiful expression of Israel’s longing for Yahweh and his saving actions after a great national tragedy. We have seen how the question “How long?” functions to express a human need as well as remind God to be God. The structure holds for this communal psalm. Verse nine is a powerful recounting of the state of affairs. No longer did the temple and the beautiful things that accompanied it exist. The prophets were gone. And the remnant of those who remained to mourn the loss of that which oriented their whole life did not know how long they could endure these conditions. They had come to their limits. But in verse 10, the end of human tolerance, they cry out to God for that which they do not know, “How long?” The prominence of memory, in both positive (remember) and negative (do not forget) assertions, is evident even in a cursory read. Verse two incites Yahweh to remember Israel, his chosen people, and Mount Zion, his chosen place as both have been defiled. Such is the state that gives rise to their cries. Verses 12-17 powerfully recall Yahweh’s sovereign power over primal creation wresting it from chaos. While these remembrances act on the one side as praise of God’s past action thus strengthening Israel’s hope. They also function out of a seething undercurrent of doubt and accusations flung God-ward. They are both praising and parading God’s past actions before him in the light of covenant faithfulness. This is perhaps the one of the strongest examples of the secondary text with the psalmist direct insistence that Yahweh, “Have regard for [his] covenant (vs. 20). If Yahweh does not act, it appears he is going back on his own covenant. It is a reminder to God that he once overcame the primordial chaos and that he can, and should do it on the basis of his character and covenant, once again for his chosen people. It is interesting that the psalmist points out that the covenant is Yahweh’s covenant. It is extended by Yahweh and thus he is also subject to fulfilling it. But the “thou” or “your” theme, referring to Yahweh, is upheld through out the psalm. It is Yahweh’s foes and adversaries, and not Israel’s, who have pillaged Yahweh’s people and sanctuary. It is Yahweh’s name that has suffered derision. God’s honor is on the line. But again, the secondary implications are indeed secondary to the hope Israel has in Yahweh. In one sense this psalm is about the temple and in another sense, it is not about the temple at all. Instead, it is a question of Who was to have been found there and the One who worked salvation so often in the past. Israel is claiming that Yahweh was powerful then, and despite the desecration of the temple, still is. Israel is not utterly crushed. They were still able to eek out an angry prayer to be laid at Yahweh’s throne.[5] [1] Brueggemann, Message of the Psalms, 67. [2] Westermann, The Living Psalms, 22. [3] I would suggest that this is also a dangerous endeavor in the U.S. considering the deeply enmeshed civil religion that many churchgoers participate in. [4] Brueggemann, Message of the Psalms, 68. [5] Brueggemann, Message of the Psalms, 71. Today I want to look at Psalm 13 and 62.

Psalm 13 is striking because of the sheer repetition of the “How long?” question. The question is employed four times in the first two verses asking about God’s memory of the psalmist, God’s presence/absence, the Psalmist’s resulting sorrow from God’s absence and forgetfulness, and the proximity of the Psalmist’s enemies. In this psalm, we can clearly see Westermann’s three participants. Though the three are distinct, they are inseparable.[1] A polite reading suggests that the psalmist is asking for a time when life will return to the good. But if we peer closer and consider the lack of reference to sin or guilt again, we perceive an innocence on the part of the psalmist. Thus the blame is directed squarely at Yahweh for his state. The psalmist proceeds to hurl three petitionary imperatives Yahweh’s way in verse 3 to “consider,” “answer,” and “enlighten.” The psalmist also gives Yahweh a motivation, (or I will sleep the sleep of death) and the subsequent results of God’s continued inaction would result in the enemies triumphing over the Psalmist and ultimately of Yahweh’s self through his covenantal solidarity with the Psalmist. While the psalmist bemoans his current state of physical and emotional turmoil, he can still find the strength in Yahweh’s previous actions with him to offer a hope that Yahweh will once again deal “bountifully with him.”[2] There is no abandonment of God, but recalling God’s past actions, for the psalmist’s own faith strengthening benefit but for God’s apparent memory slip. This recollection before God, gives him a renewed vigor to wait until the reprieve comes in God’s saving actions. Mays notes that the Psalm is a direct address to God utilizing the “name that God has given the people for God as self-revelation...thus bestowing the possibility and promise of prayer.”[3] Even in the address to God, the psalmist is being faithful to God’s previous actions, calls God to the same focus of faithfulness to their partnership. Psalm 62 contains an interesting usage within the collection of questions. The psalm is an avowal of trust in Yahweh as the psalmist’s fortress despite the brutal warlike imagery of the enemies who besiege the walls of the city.[4] “How long will you assail a person, will you batter your victim, all of you, as you would a leaning wall, a tottering fence?” Here we see all three of Westermann’s participants present, but who is responsible for what? If we lift up the secondary implications, we begin to see that the same question may be indirectly addressed to Yahweh.[5] In this suggestion, God would be implicated by his absence for what befell the individual. And yet, I wonder can the question be directed at God? God is the subject of the immediately preceding verses and not until after verse 3 are the enemies mentioned. If the question is directed primarily at God, God would seem to be culpable for what appeared to be a lapse of protection and forgetfulness of the covenant. [1] James L. Mays, The Lord Reigns: A Theological Handbook to the Psalms, (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1994), 55. [2] Craigie, 141. [3] James L. Mays, Psalms, Interpretation, (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1989), 78. [4] Marvin E. Tate, Psalms: 51-100, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 20. (Dallas: Word Books, 1990), 121. [5] Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament, 319. Have you ever looked at your bookshelf and imagined the the authors who penned all those glorious texts actually sitting on your shelf? I have. The next obvious question, at least to me, is who are they sitting next to? What kind of conversations would they have? For instance, what would the black liberation theologian James Cone and the conservative Baptist theologian Millard Erickson say to one another? Or what might transpire between Rudoph Otto and James Packer? Schliermacher and Bertrand Russell?

I suppose potential fireworks of such conversations might be somewhat determined by how you arrange your bookshelves. For me, it is topic by author. So in many ways, by arranging them topically they are already in some measure of communication. Another variable might be how diverse (methods, positions, chronological etc) your library is. If I were to arrange the total library alphabetically, there could make some great conversations between theology and the arts. But then again, I am really into eavesdropping on the Cone/Erickson debates.  PDF? What the frack is PDF you ask? It does not stand for "portable document formula" you may have initially surmised. PDF is a complicated condition akin to PDA or the public display of affection. Here it is the public display of faith...PDF for short. Now I must say at the outset that I am not a Broncos, Gators, or even a Tim Tebow fan really but I have been paying attention to the caustic comments that emerge around his name. It seems to me that folks cannot help themselves when it comes to critiquing Tebow. But it goes well beyond his football skill (or lack of skills depending upon who you ask). It is simply shocking to me how vitriolic people become over this man who has actually played very little professional football. He has done nothing to embarrass the organization, his teammates, fans, family. He is humble. He by all accounts seems to live up to what he says. He has played fairly well. But why the constant harsh critiques that go beyond the level of other players? I am not alone in noticing this phenomena either? I've run into a couple posts over on Fox Sports from Jenn Floyd Engel (Article 1) (Article 2). Here is another interesting video calling for an end to Tebowing (Video) Jon Malesic however, provides a provocative take on why Tebow is such a target. http://www.atthispoint.net/articles/touchdown-jesus-on-the-wages-of-discipleship-in-america/210/ Another great article along these lines is UND alum, Chuck Klosterman wrestling with the issue of faith says, "But the real reason this "Tebow Thing" feels new is because it's a God issue that transcends God, assuming it's possible for any issue to transcend what's already transcendent. I'm starting to think it has something to do with the natural human discomfort with faith — and not just faith in Christ, but faith in anything that might (eventually) make us look ridiculous." This collection of articles tells me or reminds of several things I already knew. Tim Tebow loves God. Faith and/or religion in public is still controversial. The Klosterman article is interesting. He notes how another former NFL quarterback, who is also a Christian said Tim might tone down his public displays of faith. While Tebow's response is initially a nice retort that you wouldn't tell your spouse you love them only on your anniversary. This seems to justify the frequency of Tebows acknowledgements of his faith and God's goodness. But Klosterman fails to note the means by which Tebow does so and its appropriateness. While it is a great practice to tell your spouse that you love them daily, there are ways in which that sentiment should be carried out and ways that should not be done. A message in the sky pulled from a plane is not necessary or appropriate. A dozen roses delivered to their place of work every day is not necessary or appropriate. Nor song dedications on the local radio stations, billboards, television commercials and the like. I questions Tebow's sense of judgment about such appropriateness. His actions, while well intentioned and most likely rooted in a deep faith, have drawn criticism and mockery upon himself (which I am sure he takes in stride as part of the perception of being a persecuted minority) but also upon an ancient and holy faith. There is a big difference of telling your spouse or God how much you love them at home in the morning, afternoon, or evening than in front of other people...particularly thousands of football fans in the stadium and around the globe through television and the internet. Here is where aspects of Jon Malesic's work can enter. Should Tebow share pieces of his faith so publicly to a public that in many ways despises those sacred symbols? To borrow a biblical allusion, is he threatening the sacredness of the faith by throwing "pearls before the swine"? Klosterman is right to note this sense of the persecuted minority Evangelicals often feel, but he also fails to note how ideas of evangelism are so tightly wound into the Evangelical imagination and public practice of the their faith. I suspect that relatively few Christians would encourage evangelism methods of street corner preaching, sandwich boards, roadside signs etc. Perhaps these methods had their place at one point in time, but I suspect that many would say that they are ineffective, and can actually bring negative associations and harm upon the faith. I think Tebow is a genuine guy, a great athlete, a faithful Christian who has, because of his athletic prowess and celebrity, a particular prominent position for evangelism. I would encourage him, to consider the times and means by which he expresses his love of and faith in God. Continuing on in the questioning of God in the Psalms, I hope to explore several individual Psalms. Psalm 6 seems like a good place to start.

Peter C. Craigie calls Psalm 6 a psalm of sickness[1] that affects both body and soul. It is quite easy to imagine the state of the individual, near death, crying out to God for help and health. The question in vs. 3 says, “My soul also is struck with terror, while you, O Lord, how long?” This question, among others, is particularly evocative. The psalmist, “gasping as a stammerer”[2] cannot even finish the question. It is a poetic portrayal of the psalmist desperation and critical state. However, Mays notes that this state of affliction is not “mutely accepted” but is opposed to it by saying, “‘Don’t…heal…turn…save,’ the prayer pleads, as though it were certain that God’s usual and preferred way with human beings favored health and life.”[3] Such fear of death and discipline has brought the psalmist to plea his case. We see the theme of the righteous sufferer emerge in verses one and two for the request not to rebuke or discipline the psalmist in God’s anger. From this perspective, we can see the underlying question of protest. If the psalmist is innocent, and there is no direct confession of sin in the psalm,[4] then it seems to implicate Yahweh in his sickness. Craigie notes that the psalmist’s plea for deliverance in vs. 4-7, “Return, O LORD, save my life” is based on God’s “steadfast” or covenant love.[5] Yet the underlying implication is that God has deserted him. Within Psalm 6 is the profound role of memory that was noted in the beginning. Verse 5 states, “In death there is no remembrance of you.” The question functions liturgically where Israel’s memory of God’s past action brings about praise. But the re-enacting of human memory before God, also reminds God of his past actions and covenant.[6] It is a reminding God to be God. This psalm is also a fine example of Westermann’s three-fold typology of participants: Yahweh, humans, and enemies. Verse 8-10 introduces the enemies as the third participant. But in the course of the psalm, God has heard the plea and protest and come to the aid of the psalmist and thus vanquishing also his enemies. That which was offered in plea and protest successfully motivated Yahweh to act on his behalf. [1] Peter C. Craigie, Psalms: 1-50, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 19, (Waco, TX: Word Books Publisher, 1983), 91. [2] Artur Weiser, The Psalms, (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1962), 130. [3] Mays, 60. [4] Weiser states, “The recognition of the psalmist’s sinfulness indeed forms the background of the psalm and is implied within it, but the actual confession of sin is entirely lacking” (Weiser, 130). Craigie also mentions the possible sin interpretation but prefers the “righteous sufferer” interpretation (Craigie, 92). [5] Craigie, 92-93. This is one of the generalizing adjectives that became normative for Israel’s speech about who Yahweh was. See Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament, 213 and note 12. [6] Craigie, 93. Continuing on in this series:

Claus Westermann argues that there are typically three main participants in protests and laments: Israel, who speaks the protest and petition; Yahweh, who is being addressed; and often the enemy, whom Israel is seeking help against.[1] Yet these forms appear with variations between the individual and corporately enacted psalms. Westermann has said that the individual is still never an “isolated individual standing alone” rather he is always in some relations to another.[2] He builds on that saying, “prayer always has a communal or social aspect: a man is never alone with God…Here we see social relationship, in sharp contrast to any idea of an inner piety: living with God cannot be separated from living with others, the two belong together.”[3] These are encouraging and needed words in our radically individualistic culture. Westermann also points out that the three participants mirror a unified nature of humanity: theology (God), sociology (others), psychology (self).[4] By way of example, if the psalmist is facing death, it is not as an isolated entity. He does so as a member of a community. But as the faithful one faces the realities of death, it leads them to ask “why” and question the nature or source of the suffering, and thus drawn to God. The “how long” form is the second most frequent question of God, to the “why” question posed to and at Yahweh in an apparent long enduring of suffering. The “How long?” questions ask about the absence of God and are predominated with terms of anger.[5] Within the communal lament, God is often portrayed as the direct or indirect cause of the current distress, often including clashes with the enemies.[6] Westermann notes that these complaints against God “tread that thin line between reproach and judgment. But never do they condemn God, for the utterances are never objective statements.”[7] And despite all the confusion and frustration the psalmist feels, they are never portrayed as abandoning God. The psalmist’s suffering is the second participant in lament psalms and occupies a less significant role than the complaint against Yahweh, though the two are intimately bound together. The corporate lament is often tinged with both suffering and disgrace of the second participant. While a little more complicated in the lament of the individual, the causes of distress vary from physical and spiritual suffering, the immanence of death, and more general laments.[8] Complaints about the enemy, the third participant in laments, occur in both individual and corporate experiences. The enemy constitutes a basic component during times of war and is closely related to the corporate complaint against God. Often the accusation against the enemy contains two foci: a) what they have done to Yahweh’s people, and b) their slander and abuse.[9] In the individual experiences of the enemy, statements often concern either an act of the enemy upon the lamenter (which are most frequent) or are statements about the nature of the enemy.[10] [1] Westermann, Praise and Lament in the Psalms, 169, 174-194. See also Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament, 375. Also Philip S. Johnston seems to utilize Westermann’s 3-fold typology but renames them “agents of distress” in Interpreting the Psalms: Issues and Approaches, ed. David Firth & Johnston (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2005), 74-78. [2] Westermann, Praise and Lament in the Psalms, 170. [3] Westermann, The Living Psalms, 70. [4] Ibid., 70. [5] Westermann, Praise and Lament in the Psalms, 177. [6] Johnston, in Interpreting the Psalms: Issues and Approaches, 74. [7] Westermann, Praise and Lament in the Psalms, 177. Does this mean they are just emotional eruptions? How seriously does God take them then? [8] Ibid., 186. [9] Ibid., 180. [10] Ibid., 189-194. The question, “How long” seems to function with two different, but interrelated, intentions. Israel’s questions were not abstract or generic musings, but were immersed in concrete life experiences. First and foremost, the queries are pleas from the rugged and overwhelming depths of human experience to the One whom they trusted could rectify their situation. And yet, they are not simply about receiving a time-table from God. While the questions are in one sense, an avowal of trust that Yahweh is good and faithful and will act on their behalf, experience and expectation do not always meet. Brueggemann states:

"Israel is profoundly aware of the incongruity between the core claims of covenantal faith and the lived experience of its life. Covenantal faith had dared to make the claim that the world is completely coherent under the rule of Yahweh, so that obedience leads to shalom. Israel’s lived experience, however, makes clear that an obedient life on occasion goes unrewarded or even suffers trouble in ways that should not have happened.”[1] Within this disparity, the questions function secondarily to probe Yahweh’s actions and various states of “hiddenness, ambiguity, instability, or negativity.”[2] Israel’s position, which generates the plea, is also a near indictment of Yahweh’s lack of accountability and responsibility in their state, in contrast to that which was promised them. It is a critical comment on the covenantal relationship. Israel’s interrogations seem to ask if their covenantal partner is faithful. Are Yahweh’s self-revelations in word and deed are ultimately correlative of Yahweh’s character? Israel, having accepted what Brueggemann terms the normative adjectives from Exodus 34.6-7[3] (merciful, gracious, slow to anger, steadfast love, abounds in faithfulness, forgiving) as central testimony about who Yahweh is, calls these very same things into question in their cross-examination of Yahweh.[4] We begin to see that Israel’s questions are not only to Yahweh about their suffering state, but accusatorily at Yahweh for perceived infidelity to the covenant and Yahweh’s own self revelation and character. The seriousness of Israel’s petition to God is now escalated to confrontational levels in hopes to engage Yahweh.[5] It is proper to examine the question in other non-psalmic scripture to see if the dual functions follow. We see the question asked by both Yahweh and Joshua as a rebuke of Israel in Exodus 16.28; Numbers 14.11, 27; Joshua 18.3. Also, shows up in Moses attempt to aright Pharaoh in Exodus 10.3; as Eli censures Hannah in 1 Samuel 1.14; and in Job’s interactions with his critics in 8.2 and 18.2. Gerstenberger notes that all of these instances introduce “reproachful speech apparently after repeated efforts to amend the situation have failed...The undertone in all these passages is that a change is overdue.”[6] And yet it is the very serious state of crisis which propels Israel to approach Yahweh in simultaneous speech of hope and doubt of Yahweh’s true integrity. The laments and complaints speak both about the utter collapse of all poles of orientation and yet claim that Yahweh, though perhaps not hidden, is still in control.[7] But then again, if Yahweh is in control, he is either explicitly or implicitly responsible for their misfortunes. It is an insistent and forceful hope where the crisis of doubt proves Israel’s faith. The lament structure itself seems to lead the speaker into, through, and out of the darkness.[8] Thus Israel’s hopeful plea to Yahweh, out weighs the underlying critique. It is a hopeful appeal and provocation for Yahweh to remedy the unbearable situation on the basis of covenantal faithfulness and Yahweh’s own integrity.[9] [1] Walter Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1997), 378-9. [2] Ibid., 318. [3] Exodus 34.6-7 - The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, yet by no means clearing the guilty, but visiting the iniquity of the parents upon the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation. [4] Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament, 213-14. [5] I cannot help but to wonder if this is Israel’s attempt at manipulating Yahweh to action with the threat of maligning his character. [6] Erhard S. Gerstenberger, Psalms: Part 1 With an Introduction to Cultic Poetry, Vol. XIV, The Forms of the Old Testament Literature, (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1988), 84. [7] Brueggemann, Message of the Psalms, 54. [8] Ibid., 54. [9] There seems to be some debate over the categorization many of the Psalms. While lament is one of the main categories, Westermann suggests that the “appeal” to God represents the core of the lament psalm. Westermann chooses to retain the traditional wording, with this point having been made. Claus Westermann, Praise and Lament in the Psalms, (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1981), 33-34. While Brueggemann would like to make another subdivision or clarification, not on petition, but like more in line with provocation regarding the complaint nature of the psalms. He states, “It is important to note that these psalms are indeed voices of complaint or judicial protest, and not lamentations, as they are often called” (Brueggemann, Theology of the Old Testament, 374). |

Ryan StanderArchives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed