|

The exhibit, Graphic Radicals: 30 Years of World War 3 Illustrated, features highlights from the independent political cartooning magazine World War 3 Illustrated. The exhibit includes original artwork about events that artists have scrutinized, documented and participated in over the last three decades.

Graphic Radicals: 30 Years of World War 3 Illustrated opens on September 28 at two galleries in Grand Forks: the Colonel Eugene E. Myers Gallery on the UND campus and the Third Street Gallery on Kittson, and continues through October 31. The opening receptions are Wednesday, October 26, 2011, beginning at the UND location from 4:30 – 6:00 p.m., then the Third Street Gallery, downtown Grand Forks, from 7 – 9:00 p.m. Artists Seth Tobocman, Sabrina Jones and Peter Kuper will be in attendance. World War 3 Illustrated was established in 1980 in New York City in by artists Peter Kuper and Seth Tobocman in response to the Iran hostage crisis and the election of Ronald Regan. Since that time, the publication, produced annually, includes artwork – created by a collective of artists - that confront social and political issues on a specific theme. Themes addressed in World War 3 Illustrated include wide-ranging subjects such as racism, prison, AIDS, religion, sex and war. The publication has also addressed specific events, such as the Tompkins Square Riot, responses to September 11, a teacher’s strike in Mexico and hurricane Katrina rescue efforts. The artwork presented in each issue received critical success. Holland Carter, writing in a New York Times review of the exhibition, observes that “The 9/11 issue, which appeared very soon after the disaster, is still a heart-stopper, with its diary-like narratives in cartoon form and its evocation of the grief and paranoia that gripped the city”. Artists featured in Graphic Radicals: 30 Years of World War 3 Illustrated created powerful responses to critical contemporary events. Critic Lucy Lippard notes that the “ecological and social prophesies [presented in World War 3 Illustrated] are coming to pass, and the apocalyptic vision that gives WW3 its desperate force and unique identity is the present”. In an early publication, World War 3 Illustrated captured the dangerous, apocalyptic atmosphere of the New York City during the Tomkin Square riots. In the most recent issue featured in the exhibit, contributing artists captured the national mood of economic and ecological distress by offering proposals for progress that may improve the state of the nation. Graphic Radicals: 30 Years of World War 3 Illustrated features paintings, comics, murals, film, animation and drawings from 40 artists that contributed to World War 3 Illustrated. Among the artists represented in the exhibition are Art Speigelman, Sue Coe, Eric Drooker, Mac McGill, Sabrina Jones, Keven Pyle, Rebecca Migdal, James Romberg and Marguerite Van Cook. There are over 150 works of art included in the exhibition; the work is presented in a thematic, chronological manner. Graphic Radicals: 30 Years of World War 3 Illustrated is on loan from the Exit Art cultural center in New York City. Exit Art present experimental, historical and unique presentations of aesthetic, social, political and environmental issues. The exhibit is curated by Peter Kuper, Seth Tobocman and Susan Willmarth. The exhibition is free and open to the public. A panel discussion featuring artists Peter Kuper, Seth Tobocman and Sabrina Jones will be held on Tuesday, October 25 at 3:00 p.m. at the University of North Dakota Memorial Union, River Valley Room. For more information, contact Kim Fink, 777-2905 or Joel Jonientz, 777-3395.

0 Comments

Life is busy. Of course the is little need to state the obvious here. We are all busy I suspect. Busy trying to keep balance in our lives for the things and people that matter most...job, studies, family, friends, church etc. I would love to give myself wholly to any of these things...but alas survival in grad school does not allow it. So...I try to keep the proverbial plates spinning. In spite of their wobbling...they are still spinning.

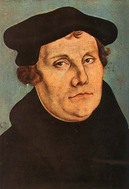

Right now, this little posting constitutes a break from a 13+ page bibliography project for my Historical Methods course. While this document will be of immense help for future research, I wish I could leave for the studio, go for a run, go see friends or family. I have the daily work at the Grad School and my weekly assignments, but there are the PhD, Fellowship, Residency applications all coming due as well on the longer range calendar (which are actually more important but get shoved to the periphery because of the amount of daily and weekly responsibilities). This week, the art department is hanging the World War III retrospective which I will spend part of the day tomorrow helping to hang. This weekend we printed for Peter Kuper who will be attending next month for the show closing. We anticipate printing for other of the artists visiting as well. Oh...and Ive been invited into 2 other print exchanges, plus my printing responsibilities for the semester credits that I am taking. It seems that while I thrive under pressure, I am nearing a point where I no longer enjoy the pressure as I did during the MFA. Perhaps it never goes away, but it would be nice for a season anyway to really relax and "be". But, i despite my rambling post, lamenting the fact that I am busy, I am so incredibly thankful that my past hard work has paid off in getting me more, and better opportunities. I am thankful for a growing CV, mentors and their encouragement, the support of my loving wife, and slowly sinking into a new worshipping community where all of those other burdens of my life can be left on at the altar. Well, I turned in the first draft and got some feedback and subsequently made a few changes. I think the 2nd draft is a better attempt, as it should be, as it attempts to articulate less of the Reformation's spread, and suggest a few more of the social implications. I also squeezed in a small section about the counter Reformation and the 30 years war...its amazing what you can do in 1,000 words. Protestant Reformation: Between the 14th and 17th Centuries, the Protestant Reformation introduced profound changes upon European religious, social and political life. While the reformers spiritual impetus sought a re-definition of salvation and ecclesial authority, they simultaneously reshaped both political autonomy and authority of the populace. Initial steps of reform are widely attributed to the English philosopher John Wycliffe (c.1330-84) and the Bohemian priest Jan Hus (c.1372-1415). Their followers, the Lollards and Hussites respectively, anticipated many of the Reformations’ central theological tenants of personal faith, centrality of scripture, and vernacular liturgy while resisting papal authority, celibacy, transubstantiation, and indulgences. While such critiques were hardly new, Martin Luther (1483-46) intensified this spirit of reform in Germany. Luther’s biblical studies convinced him that salvation came by faith and not by works as emphasized within Medieval Catholic theology. Rome instituted a new indulgence, or financial donation to church remitting sin or release from purgatory, collected by John Tetzel (1465-1519) to complete St. Peter’s Basilica and to repay debts for purchasing the Archbishopric of Mainz. Luther responded on October 31, 1517 posting 95 theses of theological charges upon the Wittenberg Chapel door. The Vatican denounced Luther’s positions; leading to his second conviction that scripture, not popes or councils, was the standard of faith. Having dispensed with church’s sacred hierarchy and lineage Luther emphasized the priesthood of believers thus localizing church authority. Pope Leo X (1475-1521) condemned Luther’s writings and excommunicated him in 1521. Under oath to the Vatican, Charles V (1500-58) called Luther to a Diet, or official assembly, at Worms to account for his writings. Refusing to recant, Luther was summarily exiled to Saxony where he translated the New Testament, and later the Latin liturgy, into German allowing the reform to continue. Luther’s vernacular translations and emphasis on the common believer had significant political and social effects. Incited by Luther’s colleague Andreas Karstadt (1480-1541), radical reformer Thomas Muntzer (c.1489-1525) and a newly delivered authority the German peasants revolted (1524-6) against their nobility to end serfdom. Luther reacted critically to the peasants’ violent misunderstanding of his egalitarian notions claiming they applied within the church only, and not secular authorities. The German nobility crushed the insurrection with Luther’s assent. Likewise, many Lutheran leaning Princes assented to his sacred/secular political theology, which provided grounds for independence from both the pope and Charles V while giving them control over the local churches and their lands. Luther’s shift of authority to local rulers, churches, and parishioners themselves ultimately atomized the church into an age of denominationalism and the privatized faith of Modern individualism. Similarly, many reformers like Karlstadt incited extensive cultural and artistic destruction leaving the Protestant church with a legacy of cultural disengagement. In 1530, Luther’s colleague, Philip Melanchton (1497-1560) wrote the Augsberg Confession to be signed by the Lutheran Princes. However, Charles V remained unmoved in seeking to dismantle the heretical movement. In 1530 the Lutheran princes united in the Schmalkald League against the Catholic Princes. After sporadic civil wars, they signed the Peace of Augsberg (1555) allowing the princes to decide the religion of their subjects. Nearby, the Swiss Reformation birthed two central movements: the Anabaptists and Calvinists. Zurich’s Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) followed Luther’s convictions on salvation and biblical teaching, but famously denied transubstantiation in favor of a purely memorial sign. An offshoot of Zwingli’s followers called Anabaptists, meaning “re-baptizers”, introduced believers’ baptism through personal faith, rather than a requirement of state politics. Coupling the Anabaptist refusal of political oaths and the redefinition of baptism put them at odds with the state, Catholics, and reformers alike who cruelly persecuted them. In 1536, Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) convinced John Calvin (1509-64), a French scholar, to organize Geneva’s reformation. Within two years however, the city forced both to leave over Calvin’s strict theology. In 1541 Geneva’s politics shifted allowing Calvin’s return and Geneva’s emergence as a reformers refuge. Politically, Calvin’s emphasis upon on God’s sovereignty divorced the church and state legitimating government rule, while de-privileging earthly claims of absolute power. In England, politics of royal succession, more than theology, initiated reform movements. Failing to produce a son, King Henry VIII (1491-1547) sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536). Politically, the Pope resisted; however, Henry secretly married Anne Boleyn (1501-36) in 1533. The King then arranged Thomas Cranmer’s (1489-1556) appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury who subsequently annulled his first marriage. Both were swiftly excommunicated, forcing Henry’s hand in the Act of Supremacy (1534) which challenged papal supremacy by severing Roman ties and establishing the Church of England. Henry, now church head, upheld orthodox Catholic doctrine in the Six Articles of 1539. Cramner continued reform uniting aspects of Calvinism and Catholicism by translating the liturgy into the English Book of Common Prayer. Following Henry’s death in 1547, Cramner’s Protestantized Forty-Two Articles replaced the Six Articles of Henry’s Catholicism. Mary I (1516-58) ascended to the throne and earned the title “Bloody Mary” for her persecution of Protestants including the martyrdom of Cramner. Elsewhere, Calvinist reformer John Knox (1514-72) led the Scots to resist Mary’s Catholicism amidst a civil war by likewise drafting articles of religion outlawing Catholicism. Following Mary’s violent reign, Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth I assumed the throne. Her Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) allowed the Church of England to fully embody its distinctive, and politically necessary, character as a via media between Catholicism and Protestantism. Yet Elizabeth’s reforms were not enough for the more radical Puritan Protestants who criticized both church and state, while emphasizing a Congregationalist church government and strict personal piety. Luther was intent on reforming Catholicism, not causing a schism, he did inspire a counter, and concurrent, reform within Catholicism. The Council of Trent (1545-63) clarified and united Catholic doctrine against the Protestant contests. In spite of the Peace of Augsburg, skirmishes continued and culminated in the 30 Years War (1618-48). Beginning in religion and ending in a political stalemate, the Treaty of Westphalia gave recognition to Calvinists, Lutherans and Catholics to reciprocally worship in the others lands. Further Reading: Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformations, 2nd ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Lindberg, Carter, ed. The European Reformations Sourcebook, London: Wiley- Blackwell, 2009. MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation, New York: Penguin, 2005. McGrath, Alister E. Reformation Thought: An Introduction, 3rd ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2001. Pettegree, Andrew, ed. The Reformation World, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2001.  This week, for our Historical Research Methods course, our assignment is to write a 1,000 encyclopedia entry on a list of impossibly broad topics that range from the Holocaust to the Industrial Revolution. I was thankful that there was at least one topic of more familiarity to me: the Protestant Reformation. I figured that even though it is impossibly broad, I had a better shot at it because of my theological training and I had both significant and quality sources to skim at my fingertips. So I was able to finish the entry today before, during (I was too frustrated that I had to leave) and after the Hawkeye game (an amazing 4th quarter come from behind victory). The only thing left to do is create a list for further reading. Without further delay...here it is (be kind): The Protestant Reformation generally describes a series of profound religious, social and political changes that swept across Europe between the 14th and 17th Centuries.

Initial steps of reform are widely attributed to the English philosopher John Wycliffe (c.1330-84) and the Bohemian priest Jan Hus (c.1372-1415). Their followers, the Lollards and Hussites respectively, anticipated many of the Protestant Reformations’ central theological tenants basing their teaching on personal faith, centrality of scripture, and vernacular liturgy while resisting papal authority, celibacy, transubstantiation, and indulgences. While such critiques were hardly new, Martin Luther (1483-46) intensified this spirit of reform in Germany. Luther’s biblical studies convinced him that salvation came by faith and not by works as emphasized by Rome. He challenged Rome’s position on indulgences, once instituted to fund the Crusades, in particular, Dom. John Tetzel’s (1465-1519) papal collection for the completion of St. Peter’s Basilica in 1517. On October 31, 1517 Luther posted 95 theses of theological charges upon the Wittenberg Chapel door. The Vatican denounced Luther’s positions; leading to his second conviction that scripture, not popes or councils, was the standard of faith. Having dispensed with church’s sacred hierarchy and lineage Luther emphasized the priesthood of believers thus localizing church authority. Pope Leo X (1475-1521) condemned Luther’s writings and excommunicated him in 1521. Under oath to the Vatican, Germany’s emperor, Charles V (1500-58) called Luther to a Diet at Worms to account for his writings. Refusing to recant, Luther was summarily exiled to Saxony where began translating the New Testament, and later the Latin liturgy, into German allowing the reform to continue. Luther’s vernacular translations and emphasis on the common believer had significant political and social effects. Incited by Luther’s colleague Andreas Karstadt (1480-1541) and the radical reformer Thomas Muntzer (c.1489-1525), the German peasants began a resistance revolt (1524-6) against the their nobility seeking the end of serfdom. Luther reacted critically to the peasants’ violence and misunderstanding of his egalitarian notions claiming they applied within the church only, and not secular authorities. Luther gave his assent to the German nobility who crushed the insurrection. Likewise, many Lutheran leaning Princes assented to his sacred/secular political theology, which gave them grounds for independence from both the pope and Charles V while giving them control over the local churches and their lands. In 1530, Luther sent Philip Melanchton (1497-1560) to an assembly in Augsberg where he wrote the Augsberg Confession to be signed by Lutheran Princes. However, Charles V remained unmoved in seeking to dismantle the heretical movement. In 1530 the Lutheran princes united in the Schmalkald League against the Catholic Princes. After sporadic civil wars they signed the Peace of Augsberg (1555) allowing princes to decide their subjects religion. As a result, Lutheranism spread across much of Germany and Scandinavia. The Swiss Reformation birthed two central movements: the Anabaptists and the Calvinists. Zurich’s Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) followed Luther’s convictions on salvation through faith and biblical teaching, particularly the Old Testament. Zwingli famously denied transubstantiation in favor of a purely memorial sign. An offshoot of Zwingli’s followers shifted focus to the New Testament emphasizing a believers’ baptism through personal faith, rather than a requirement of state politics. These Anabaptists’, meaning “re-baptizers,” anti-political refusal of oaths and their redefinition of baptism put them at odds with the state, Catholics, and reformers alike who cruelly persecuted them. In 1536, John Calvin (1509-64), a French scholar, was convinced by Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) to organize Geneva’s reformation. Two years later, both were forced to leave over Calvin’s strict theology. In 1541 Geneva’s politsic shifted allowing Calvin’s return and Geneva’s emergence as a reformers refuge. Calvin’s emphasis on God’s sovereignty divorced the church and state legitimating government rule, while de-privileging earthly claims of absolute power. Calvinism spread to France, the Netherlands and Scotland. The initial English Reformation was motivated more by politics of royal succession than theology. Failing to produce a son, King Henry VIII (1491-1547) sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536). Politically, the Pope resisted and excommunicated the King following his secret marriage to Anne Boleyn (1501-36) in 1533. The King arranged Thomas Cranmer’s (1489-1556) appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury who subsequently annulled the King’s first marriage. Both were swiftly excommunicated forcing Henry’s hand in the Act of Supremacy (1534) which challenged papal supremacy by severing ties and establishing the Church of England. Henry, now church head, upheld orthodox Catholic doctrine in the Six Articles of 1539. Cramner translated the liturgy into English, established the Book of Common Prayer uniting aspects of Calvinism and Catholicism. Following his death in 1547, the Six Articles of Henry’s Catholicism were repealed and replaced with Cramner’s Protestantized Forty-Two Articles. Mary I (1516-58) ascended to the throne and earned the title “Bloody Mary” for her persecution of Protestants including the martyrdom of Cramner. Elsewhere, Calvinist reformer John Knox (1514-72) led the Scots to resist Mary’s anti-Christian/Catholicism amidst a civil war by likewise drafting articles of religion for the Parliament to outlaw Catholicism. Following Mary’s violent reign, Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth I assumed the throne. Her Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) allowed the Church of England to fully embody its distinctive, and politically necessary, character as a via media between Catholicism and Protestantism. Yet Elizabeth’s reforms were not enough for the more radical Puritan Protestants who criticized both church and state, while emphasizing a Congregationalist church government and strict personal piety. The Reformation has a mixed legacy. While inspiring needed reforms, it also caused significant continental conflict that changed the very fabric of political and social life. Protestants inspired reform within Catholicism itself, however, syncretism and superstitions within the populace persisted. In spite of the religious Utopian aspirations, the reformers introduced a secular state that redefined religion’s public practice. The reformers challenges of authority atomized the church by transferring authority to individuals thus splintering the church into an age of denominationalism. Similarly, despite the re-invigorated scholarship of religion, many reformers incited extensive cultural and artistic destruction leaving the Protestant church with a legacy of cultural disengagement. When I left for Cyprus, I really had no idea what I was getting into or what the body of work would look like. I had vague ideas of the human fingerprint upon the landscape and the distance between the contemporary and ancient records made upon/within the landscape.

When I got there, I began looking for how we were marking the land in search for the historical marks. And with this perspective, several shots became especially poignant. This one in particular conveys those ideas. Here the literal footprints imprinted upon the landscape divide two forms of trash: one contemorary, one ancient. Both offer some sort of record of human presence illustrated by the ephemerality of the footprints in the dirt. Here the two worlds become condensed into one shot. What is striking to me about this, is how these ideas pass over into the theory of history, hermeneutics and beyond. Here we can see, literally see, our impact upon our studies. We cannot ignore our our own presence, presumptions, pe within our research. The photo embodies my hopes for the overall residency, with a touch of humor as well. A few years ago I had the great opportunity to teach a theology and film course at Sioux Falls Seminary. It was my last semester of working there as an admissions counselor before we moved to North Dakota for me to pursue the MFA. Now that I am done with the MFA and have enrolled into a MA in History program here at UND, I may have the opportunity once again to teach at SFS. I approached Dr. Susan Reese at the seminary to see if she would be interested in co-teaching a course on vocation and film. So together we crafted a syllabus and submitted a proposal. I am glad to say that it was approved a few weeks ago. So, now begins the fun work of catch up reading and re-reading on the two conversations and how they will be brought together.

In that first class, one week of the semester we looked briefly at the idea of vocation and watched Billy Elliot and The Apostle. I suspect both will be making a return showing in the syllabus, but we are exploring a few others as well. I've been excited about the idea of teaching lately...perhaps it is the "out of place" feeling I have being in a course in a new discipline. But perhaps there is something else going on too. Perhaps my heart is changing on the idea of further study and the desire to teach sooner rather than later...it certainly pays better than being a graduate student. There is an irony at play here it seems that this course on vocation seems to bringing about in the way of unsettling the ideas of my own vocation. To be continued... The famed photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson spoke of the "decisive moment" saying, "There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative," he said. "Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever." I have missed hundreds of shots because of this fleeting nature of movement of people, objects, light and any other number of variables. I have also just left the scene of a potential photograph wishing later that I had just shot it. This is one of those photos that I am so glad that I shot.

The cars are essential aspects of the project for getting groceries to hauling the team back and forth to the site, and general travel around the island visiting other sites. They take a beating and need a good cleaning when we are done. But there is something beyond the necessity of the cars that endears this photograph to me. I suppose it is the humor of it...something reminiscent of Elliot Erwitt perhaps. What are the odds that these cars would stop, equal distances among them, and be left on the site with the hatch wide open? It is perhaps the decisive moment in the reco One of the most striking things to me about this space was the ancient debris littering the surface. It would likely be surprising for North Americans, let alone Iowan's like myself, to find a single piece of an ancient amphora handle in their field. So the sheer volume of pottery shards scattered over the surface was astounding to me. On one of my first trips out to site, my head still floating somewhere over the Atlantic, I sat down in the heat of the afternoon and just began to collect the pieces within an arms reach of where I sat and photographed them. I did this several times finding both fine and coarse ware that had worked itself up to the surface from time, erosion and with the farmers help. I surprised by the density objects on the surface, their diversity, and the very fact that I could pick up these ancient pieces of pottery.

The image above is one of two composites like this that were a part of the show. My hope with these images was to record my first engagements with the ubiquitous debris at this site in a non-scientific or archaeological sense. Instead to suggest the wonder in a Iowa farmers son at the geographic and temporal distance between the hands that made these objects and my own now holding them. |

Ryan StanderArchives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed