This week, for our Historical Research Methods course, our assignment is to write a 1,000 encyclopedia entry on a list of impossibly broad topics that range from the Holocaust to the Industrial Revolution. I was thankful that there was at least one topic of more familiarity to me: the Protestant Reformation. I figured that even though it is impossibly broad, I had a better shot at it because of my theological training and I had both significant and quality sources to skim at my fingertips. So I was able to finish the entry today before, during (I was too frustrated that I had to leave) and after the Hawkeye game (an amazing 4th quarter come from behind victory). The only thing left to do is create a list for further reading. Without further delay...here it is (be kind): The Protestant Reformation generally describes a series of profound religious, social and political changes that swept across Europe between the 14th and 17th Centuries.

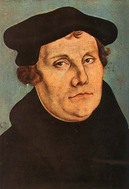

Initial steps of reform are widely attributed to the English philosopher John Wycliffe (c.1330-84) and the Bohemian priest Jan Hus (c.1372-1415). Their followers, the Lollards and Hussites respectively, anticipated many of the Protestant Reformations’ central theological tenants basing their teaching on personal faith, centrality of scripture, and vernacular liturgy while resisting papal authority, celibacy, transubstantiation, and indulgences. While such critiques were hardly new, Martin Luther (1483-46) intensified this spirit of reform in Germany. Luther’s biblical studies convinced him that salvation came by faith and not by works as emphasized by Rome. He challenged Rome’s position on indulgences, once instituted to fund the Crusades, in particular, Dom. John Tetzel’s (1465-1519) papal collection for the completion of St. Peter’s Basilica in 1517. On October 31, 1517 Luther posted 95 theses of theological charges upon the Wittenberg Chapel door. The Vatican denounced Luther’s positions; leading to his second conviction that scripture, not popes or councils, was the standard of faith. Having dispensed with church’s sacred hierarchy and lineage Luther emphasized the priesthood of believers thus localizing church authority. Pope Leo X (1475-1521) condemned Luther’s writings and excommunicated him in 1521. Under oath to the Vatican, Germany’s emperor, Charles V (1500-58) called Luther to a Diet at Worms to account for his writings. Refusing to recant, Luther was summarily exiled to Saxony where began translating the New Testament, and later the Latin liturgy, into German allowing the reform to continue. Luther’s vernacular translations and emphasis on the common believer had significant political and social effects. Incited by Luther’s colleague Andreas Karstadt (1480-1541) and the radical reformer Thomas Muntzer (c.1489-1525), the German peasants began a resistance revolt (1524-6) against the their nobility seeking the end of serfdom. Luther reacted critically to the peasants’ violence and misunderstanding of his egalitarian notions claiming they applied within the church only, and not secular authorities. Luther gave his assent to the German nobility who crushed the insurrection. Likewise, many Lutheran leaning Princes assented to his sacred/secular political theology, which gave them grounds for independence from both the pope and Charles V while giving them control over the local churches and their lands. In 1530, Luther sent Philip Melanchton (1497-1560) to an assembly in Augsberg where he wrote the Augsberg Confession to be signed by Lutheran Princes. However, Charles V remained unmoved in seeking to dismantle the heretical movement. In 1530 the Lutheran princes united in the Schmalkald League against the Catholic Princes. After sporadic civil wars they signed the Peace of Augsberg (1555) allowing princes to decide their subjects religion. As a result, Lutheranism spread across much of Germany and Scandinavia. The Swiss Reformation birthed two central movements: the Anabaptists and the Calvinists. Zurich’s Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) followed Luther’s convictions on salvation through faith and biblical teaching, particularly the Old Testament. Zwingli famously denied transubstantiation in favor of a purely memorial sign. An offshoot of Zwingli’s followers shifted focus to the New Testament emphasizing a believers’ baptism through personal faith, rather than a requirement of state politics. These Anabaptists’, meaning “re-baptizers,” anti-political refusal of oaths and their redefinition of baptism put them at odds with the state, Catholics, and reformers alike who cruelly persecuted them. In 1536, John Calvin (1509-64), a French scholar, was convinced by Guillaume Farel (1489-1565) to organize Geneva’s reformation. Two years later, both were forced to leave over Calvin’s strict theology. In 1541 Geneva’s politsic shifted allowing Calvin’s return and Geneva’s emergence as a reformers refuge. Calvin’s emphasis on God’s sovereignty divorced the church and state legitimating government rule, while de-privileging earthly claims of absolute power. Calvinism spread to France, the Netherlands and Scotland. The initial English Reformation was motivated more by politics of royal succession than theology. Failing to produce a son, King Henry VIII (1491-1547) sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536). Politically, the Pope resisted and excommunicated the King following his secret marriage to Anne Boleyn (1501-36) in 1533. The King arranged Thomas Cranmer’s (1489-1556) appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury who subsequently annulled the King’s first marriage. Both were swiftly excommunicated forcing Henry’s hand in the Act of Supremacy (1534) which challenged papal supremacy by severing ties and establishing the Church of England. Henry, now church head, upheld orthodox Catholic doctrine in the Six Articles of 1539. Cramner translated the liturgy into English, established the Book of Common Prayer uniting aspects of Calvinism and Catholicism. Following his death in 1547, the Six Articles of Henry’s Catholicism were repealed and replaced with Cramner’s Protestantized Forty-Two Articles. Mary I (1516-58) ascended to the throne and earned the title “Bloody Mary” for her persecution of Protestants including the martyrdom of Cramner. Elsewhere, Calvinist reformer John Knox (1514-72) led the Scots to resist Mary’s anti-Christian/Catholicism amidst a civil war by likewise drafting articles of religion for the Parliament to outlaw Catholicism. Following Mary’s violent reign, Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth I assumed the throne. Her Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) allowed the Church of England to fully embody its distinctive, and politically necessary, character as a via media between Catholicism and Protestantism. Yet Elizabeth’s reforms were not enough for the more radical Puritan Protestants who criticized both church and state, while emphasizing a Congregationalist church government and strict personal piety. The Reformation has a mixed legacy. While inspiring needed reforms, it also caused significant continental conflict that changed the very fabric of political and social life. Protestants inspired reform within Catholicism itself, however, syncretism and superstitions within the populace persisted. In spite of the religious Utopian aspirations, the reformers introduced a secular state that redefined religion’s public practice. The reformers challenges of authority atomized the church by transferring authority to individuals thus splintering the church into an age of denominationalism. Similarly, despite the re-invigorated scholarship of religion, many reformers incited extensive cultural and artistic destruction leaving the Protestant church with a legacy of cultural disengagement.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Ryan StanderArchives

January 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed